9 minutes

Hacking Farkle

Recently, my family has been playing Farkle, a simple but difficult-to-analyze dice game. Farkle has the following rules:

- At the start of the turn, each player must roll the 6 dice.

- After rolling, the player sets aside all the dice that scored.

- The player can then choose to roll again to potentially get more points or to take the points they have already scored.

- If the player rolls and scores no points, they get 0 points and their turn is over.

- If the player uses up all 6 dice, they can recycle all of them and roll all 6 again.

The ways to score are as follows (dice cannot be double counted when scoring):

| Combination | Points |

|---|---|

| Single 1 | 100 |

| Single 5 | 50 |

| Three 1s | 300 |

| Three of any other number | 100 * number |

| 4 of any number | 1000 |

| 5 of any number | 2000 |

| 6 of any number | 3000 |

| 4 of any number and 2 of another | 1500 |

| 1-6 straight | 1500 |

| 3 pairs | 1500 |

| 2 triplets | 2500 |

The winner is the first person to score 10,000 points. Being the competitive person I am, I decided to give the game some analysis and see if I could determine the expected value for a roll in order to figure out if I should roll or not. I chose to use Go for this because I figured I’d be doing a good amount of brute forcing, so I wanted a pretty fast language that I was familiar with. I also just like writing Go.

Pure Brute Force

At first, my idea was to do 2 simple things to generate expected value:

- Use backtracking recursion to generate all the possible rolls

- Find all the ways to partition the dice in each roll and take the maximum scoring partition

Starting with my backtracking method, I quickly wrote the following

func backtrack(rolls []int, toRoll int) float64 {

if toRoll == 0 {

return float64(maxScore(rolls))

}

sum := 0.0

for i := 1; i <= 6; i++ {

sum += backtrack(append(rolls, i), toRoll-1)

}

return sum / 6

}

The idea here is fairly simple: I loop through all 6 possible die rolls, sum them up, and average them. When I’ve used up all of my rolls, I score the resulting dice.

Scoring was not quite as simple as I had hoped, though. Partitioning a set is a little complicated, especially in a language like Go with no real concept of set algebra. The general algorithm I found is as follows:

- If there is only one element, return the set containing just that element. Otherwise, do the following:

- Remove the first element from the set and generate the partitions for the remaining set.

- For each generated partition, do the following

- Add the partition containing {removed element} + generated partition

- For each set in the generated partition:

- Add the partition containing {removed element + set} + generated partition \ set

func generatePartitions(rolls []int) [][][]int {

if len(rolls) == 1 {

return [][][]int{{{rolls[0]}}}

}

firstElem := rolls[0]

rest := generatePartitions(rolls[1:])

toReturn := [][][]int{}

for _, elem := range rest {

toReturn = append(toReturn, append(elem, []int{firstElem}))

for i, set := range elem {

removed := make([][]int, len(elem))

copy(removed, elem[:])

removed = append(removed[:i], removed[i+1:]...)

toReturn = append(toReturn, append(removed, append(set, firstElem)))

}

}

return toReturn

}

Then, I take all these partitions, score each one, and return the max of all the scores:

func maxScore(rolls []int) int {

max := 0

partitions := generatePartitions(rolls)

for _, partition := range partitions {

score := scoreSuperSet(partition)

if score > max {

max = score

}

}

if max > 0 {

return curScore + max

}

return 0

}

After writing this code, however, I realized that it had quite a few problems:

- Backtracking could have to check up to 6^6 (46,656) rolls

- Each roll would have to be partitioned in every way possible. This follows the Bell numbers, so in the worst case, there are 203 possible partitions to check. Combined with the previous number, in the worst case, I have to check 947,1168 partitions.

- I’m only accounting for one roll! The part of Farkle that makes it so hard to analyze is the ability to roll multiple times, but if you take a look at my code, I’m only checking the possibilities for the direct next roll.

Let’s make a checklist for things to fix:

- Be smarter than backtracking all possibilities

- Find a way to score a roll in constant time

- Account for possibly making multiple more rolls

Improving Scoring

Something didn’t sit right with me regarding how I did scoring. It seemed totally wrong that I would need to generate up to 203 combinations and take their max score. After all, I don’t consider all possible combinations when scoring my rolls playing with my family. I group the dice according to their numbers and see if the groups fit into any of the scoring categories. Turns out, that works pretty well for real scoring. Here’s what I came up with:

1. Go through all the dice and record how many of each number there are. Also record which dice appear with which frequency

func scoreRoll(rolls []int, score int, depth int) float64 {

var occurences [6]int

for _, elem := range rolls {

occurences[elem-1]++

}

var frequencies [7][]int

for i := 0; i < 6; i++ {

occurs := occurences[i]

frequencies[occurs] = append(frequencies[occurs], i)

}

...

2. Compare the frequencies against the rules of the game

I won’t include this part since it’s just a series of if/else statements. You can find the code at this iteration here if interested.

3. Count the number of remaining 1s and 5s

if occurences[0] < 3 && countIndiv {

toReturn += float64(100 * occurences[0])

numUsed += occurences[0]

}

if occurences[4] < 3 && countIndiv {

toReturn += float64(50 * occurences[4])

numUsed += occurences[4]

}

4. If there is no score, the player gets no points. Otherwise, they get their scored points plus the score they already have

if toReturn == 0 {

return 0

}

return toReturn + float64(score)

Now, I have a scoring algorithm that will work in constant time. Let’s update that checklist:

- Be smarter than backtracking all possibilities

- Find a way to score a roll in constant time

- Account for possibly making multiple more rolls

More Backtracking

Taking extra rolls into account is actually pretty simple in theory. When you score each roll, take the expected value of rolling again. If that expected value is higher than what you’ve already scored, use it. Otherwise, keep your current score. This can be simply implemented as follows:

expectedRoll := backtrack([]int{}, numLeft, int(toReturn))

if expectedRoll > float64(toReturn) {

toReturn = expectedRoll

}

I ran this code and waited. I waited some more, and I waited even longer. Looking back, I committed the cardinal sin of recursion: recursion without a base case. Each roll would check the expected value of another roll, and the cycle would infinitely repeat. To fix this, I added a simple depth parameter to backtrack and implemented it as follows:

func backtrack(rolls []int, toRoll int, score int, depth int) float64 {

if depth >= maxDepth {

return 0

}

maxDepth is just a global variable that the user sets to define how deep they want to recurse. I then pass depth into my scoring function and change my expected roll call to implement depth:

expectedRoll := backtrack([]int{}, numLeft, int(toReturn), depth+1)

Now, theoretically, I have an algorithm that’ll go to whatever arbitrary depth I want. However, upon running this, I can only go to a depth of 2 before the program explodes running time. Since I’m backtracking, each added level of depth makes the running time go up exponentially. So I’ve fixed one problem, but just amplified another. Let’s update the checklist:

- Be smarter than backtracking all possibilities

- Find a way to score a roll in constant time

- Account for possibly making multiple more rolls

Finding A Model

Faced with no idea for how to do this without backtracking, I had the idea of dynamic programming. If I could just find a decent model for the expected values, I could get rid of all the costly backtracking. I added support for command line flags and generated all the expected values from 1 to 400 with the following command (this is in fish but a similar thing can be done in bash):

for x in (seq 400)

./farkle-odds -dice 1 -score $x

end

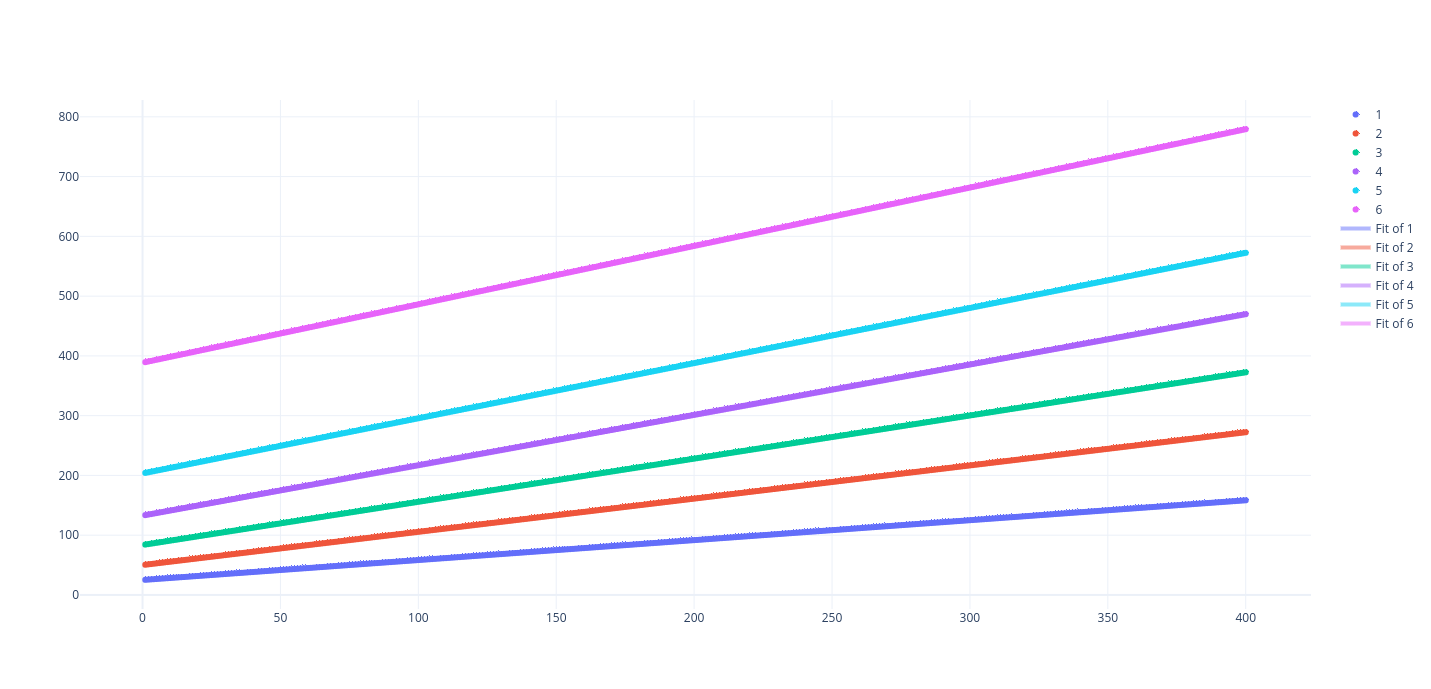

I used plot.ly to plot all this out and saw something pretty amazing:

{:width="750px”}

{:width="750px”}

It’s linear! Realizing this, I generated lines of best fit for each of the numbers of dice. I then added the approxScore method in to use the lines of best fit to approximate the expected value of a score:

func approxScore(toRoll int, score int) float64 {

return mVals[toRoll-1]*float64(score) + bVals[toRoll-1]

}

Generating Lines

After some plotting of greater depths, I concluded that the greater depths are almost linear, and any deviations from a linear model were not significant enough to substantially impact the generated expected values. Using this linearity to my advantage, I used the following algorithm to generate coefficients for a linear model for any arbitrary depth:

- Use

backtrackto find 2 expected values - Use simple algebra to find the

mandbvalues for the line between those points - Record those

mandbvalues in JSON to a file - Replace the old

mandbvalues with the new ones and repeat the process

Here’s what that looks like in actual code:

func generateCoeffs() {

for i := 1; i <= 50; i++ {

newM := []float64{}

newB := []float64{}

for j := 1; j <= 6; j++ {

// find high and low vals for this iteration

lowVal := backtrack([]int{}, j, 0)

highVal := backtrack([]int{}, j, 400)

// use high and low vals to generate line

newM = append(newM, (highVal-lowVal)/400)

newB = append(newB, lowVal)

}

coeffs.MCoeffs = newM

coeffs.BCoeffs = newB

writeVals(newM, newB, i)

}

fmt.Println("Coefficients generated and written")

}

Now, we can finally check off that last box!

- Be smarter than backtracking all possibilities

- Find a way to score a roll in constant time

- Account for possibly making multiple more rolls

Conclusion

After some refactoring, I’m really happy with the result of this little experiment. The linear model isn’t a perfect fit for the expected values, but it’s damn good and takes constant time to run.

If you’re interested in seeing what the code looks like, it can be found here. Make sure to let me know if there are any improvements I can make.

Also, here is some of the plotted data of the expected values for different dice rolls: